Creatine built its legacy in the weight room. But for women, its most powerful effects may lie beyond muscle.

Every heartbeat, every movement, every thought depends on one thing: energy. The molecule that fuels it — ATP — runs on a system that creatine keeps alive.* It’s the difference between having power on demand and running on fumes.

For women, that energy system is modulated by a distinct monthly rhythm of hormones. Estrogen and progesterone act in opposing ways to shift how the body makes and uses creatine. Across the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause, the body’s energy machinery rises and falls in rhythm with these shifting signals.

That connection is why scientists are rethinking creatine for women. Not just as a performance enhancer, but as a way to protect energy stability across every life stage.*

This article dives into the most common questions about creatine and women. Whether women really make less creatine than men, how hormones fine-tune the body’s energy network, and what changes after menopause. You’ll also learn how creatine affects mood, cognition, sleep, and bone health, and why the old myths about “bloating” miss the point entirely.*

But first, let’s talk about how creatine works.

What exactly does creatine do in the body?

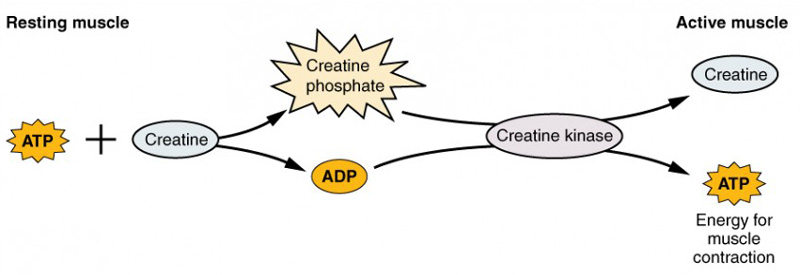

At its core, creatine is part of the body’s energy-recycling system. Everything we do depends on ATP — adenosine triphosphate — the cell’s currency of power. When energy is spent, ATP splits apart, snapping off one of its three phosphates to release a burst of energy. What’s left is ADP, or adenosine diphosphate.

The problem is, ATP reserves are limited.

That’s where creatine steps in. Stored in the body as phosphocreatine, it acts as a rapid-response reserve, donating phosphate groups to rebuild ATP the moment levels fall. The enzyme creatine kinase orchestrates this exchange, allowing cells to keep pace with sudden energy demands instead of stalling out [1].

The phosphocreatine system. Source: OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology 2e, Chapter 10.3 - Muscle Fiber Contraction and Relaxation. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

That’s why creatine is one of the most consistently effective supplements ever studied. In a large meta-analysis, it boosted sprint speed by roughly 7%, upper-body strength by 8%, and lower-body power by 14%, compared to placebo [2].

The same energy circuit that powers muscle also fuels the brain. In a placebo-controlled crossover trial of young adults with low baseline creatine levels, six weeks of creatine supplementation improved working memory by 21% and improved reasoning ability by 41% [3].

Creatine does more than supply energy. It stabilizes it, adapting to the body’s changing demands. This makes it a powerful ally across the female lifespan.*

Do women make less creatine than men?

It’s often said that women synthesize only 80% as much creatine as men. That figure is accurate…but incomplete.

Creatine balance depends on how much is made and how much is lost. In a commonly cited metabolic analysis, women’s creatine synthesis was found to average roughly 70–80% of men’s. However, their urinary creatinine excretion — the main route of creatine loss — was also lower, by nearly the same margin [4].

That makes sense, because muscle is both the primary reservoir and the primary site of creatine turnover. And since women generally have less skeletal muscle mass, their smaller daily turnover rate almost exactly mirrors their smaller storage capacity [5].

When researchers test this system directly, the “sex gap” largely disappears. In a controlled loading study, seven days of creatine supplementation increased muscle phosphocreatine equally in men and women [6]. And on a per-gram basis, women’s muscle tissue has even been found to contain about 10% more creatine than men’s [7].

Where real differences emerge isn’t in physiology. It’s in diet. Women, on average, consume 35–40% less creatine than men, largely because they tend to eat less meat and fish — the only meaningful dietary sources [8].

So the takeaway isn’t that women need more creatine. It’s that anyone who consumes less of it — for any reason — stands to gain more when they supplement.

How do estrogen and progesterone affect the body’s creatine system?

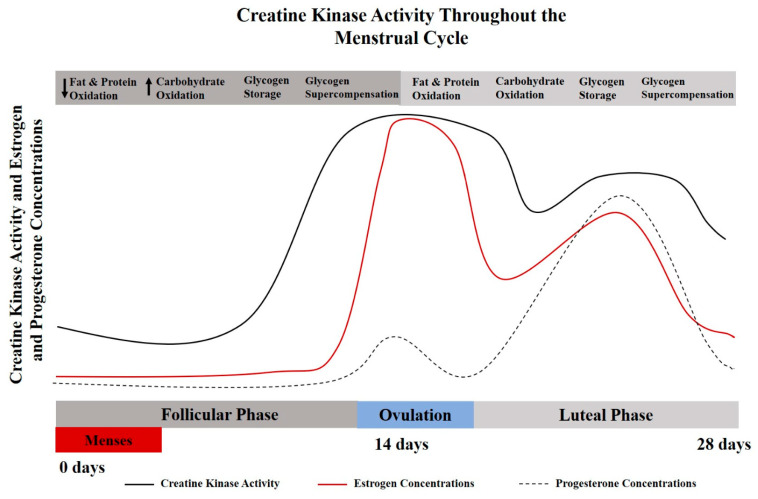

Creatine is the body’s molecular shock absorber. But this system isn’t fixed. It’s tuned by hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone, which act like opposing conductors in the body’s energy orchestra [9].

When estrogen leads, the tempo of energy metabolism quickens.

Estrogen boosts the enzymes that make creatine (AGAT and GAMT) and strengthens SLC6A8, the transporter that pulls creatine into cells [10]. Estrogen also amplifies creatine kinase (CK) activity in estrogen-responsive tissues, improving how quickly energy moves from mitochondria to where it’s needed [11].

Creatine kinase activity across the menstrual cycle. Source: A.E. Smith-Ryan, H.E. Cabre, J.M. Eckerson, D.G. Candow, Nutrients 13 (2021) 877. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

This high-estrogen tuning may help explain why women were found to have slightly higher creatine concentrations per gram of muscle.

When progesterone takes over, the tempo shifts down. It can dial back CK activity and lower the expression of GAMT and SLC6A8, slowing how creatine is made and imported into cells. The total energy relay becomes less efficient.

For women, that often translates to more draining workouts and a duller mental edge in the luteal phase. The body is conserving energy, and it feels like running through sand.

Over time, the shifts grow more permanent. As estrogen declines through perimenopause and menopause, the creatine-making enzymes quiet down and the transport gates lose sensitivity.[12].

Creatine supplementation may be especially useful here. By restoring the creatine pool when synthesis or transport slow, it helps the body keep its energetic pulse strong. To put it another way, when the natural hormonal conductors step back, creatine supplementation may keep the music playing.*

Does creatine cause water retention/bloating?

The short answer: not in the way that most people think.

If you’ve ever felt “puffy” or heavier in the week before your period, you already know what fluid retention feels like. It’s one of the most consistent effects of the luteal phase, driven largely by progesterone. As progesterone rises, it activates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, nudging the kidneys to hold sodium and water [13]. The result is more fluid outside cells and less inside them — the hallmark of that premenstrual heaviness.

That brings us to creatine. Every gram of creatine binds about 50–60 milliliters of water through osmotic pressure, which certainly sounds like a recipe for water retention. Or is it?

A recent double-blind, crossover study explored the question head-on. Thirty women completed a five-day creatine loading phase (4×5 g/day), with body water measured in both the follicular and luteal phases [14].

In the luteal phase, total body water increased by about 0.8 liters, yet body weight didn’t significantly change. What really shifted was the distribution: intracellular water rose by 0.74 liters, while only a small fraction stayed outside the cells.

Here’s why that matters. Water inside the cell is pressurized and contained, like air sealed inside a tire. It creates firmness and structure. Water outside the cell, by contrast, spreads out and pushes tissues apart — the biological version of low tire pressure.

This makes sense when we consider how creatine works. Creatine does bind water, but that fluid moves with the molecule into the cell, pulled there to maintain osmotic balance. In women, that shift reverses the typical premenstrual pattern by restoring intracellular hydration at the exact time hormones are trying to push water out.

And that intracellular hydration isn’t just cosmetic. It acts as a metabolic signal, triggering pathways that promote protein synthesis and cellular repair [15]. By increasing membrane tension and nutrient flow, it primes muscle and other tissues for growth and recovery, helping preserve lean mass and metabolic resilience.

Can creatine help women get better sleep?

Sleep problems are all too common — but they don’t affect everyone equally.

Roughly one in five adults struggles to fall or stay asleep most nights [16], and women are about 60% more likely than men to experience these difficulties [17], especially during hormonally dynamic periods like pregnancy and perimenopause.

Most explanations point to stress or lifestyle. But there may be another factor hiding in plain sight: cellular energy.

In a national analysis of nearly 6,000 adults, people who consumed at least 1 gram of creatine per day were 30% less likely to report trouble sleeping, compared to those who ate less creatine [18].

That idea was finally examined in the lab.

Researchers from the University of Idaho ran a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 21 women, each taking either 5 g/day of creatine monohydrate or a maltodextrin placebo for six weeks [19].

Participants trained twice a week with supervised resistance sessions, while their sleep was tracked nightly with Oura Rings. The researchers also controlled for menstrual cycle phase to ensure natural hormonal fluctuations were accounted for.

Women taking creatine slept about 48 minutes longer on training nights than those on placebo, averaging about 7½ hours compared to just 6½ hours in the placebo group.

Why?

During hard training, your cells burn through ATP faster than it can be rebuilt in the moment. Once phosphocreatine reserves get depleted, energy sensors such as AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) flip on, flagging an energy shortfall [20]. This in turn keeps the sympathetic nervous system firing — in effect, the biological signature of being “tired but wired.”

Creatine changes that timeline. By expanding the phosphocreatine reserve, it lets muscle and brain cells rebuild ATP more rapidly after exertion [21]. That normalization of the ATP/ADP ratio quiets AMPK activity, dampens downstream stress hormones like cortisol, and allows parasympathetic tone to rebound.

To put it more simply: creatine helps the body close the stress loop, allowing sleep to unfold instead of fighting against lingering adrenaline.*

How does creatine affect muscle after menopause?

Estrogen is far more than just a reproductive hormone. It’s a master regulator of energy in the body.

Reproduction is metabolically expensive: ovulation, pregnancy, and lactation all require enormous ATP output. So evolution made estrogen a signal that tells every tissue — from the brain to skeletal muscle — that the energy supply is adequate to support life.

Estradiol receptors sit right on muscle fibers, fine-tuning how mitochondria produce and distribute energy. Under estrogen’s direction, mitochondria generate ATP efficiently and hand it off cleanly through the creatine–phosphocreatine shuttle [22]. But as estrogen falls after menopause, that tuning slips: mitochondria leak energy and recovery slows [23].

Remarkably, a single week of creatine can move the needle — even without training.*

In one of the first studies to focus exclusively on older women, participants took creatine for just seven days. By the end of the week, they were pressing about 11 pounds more on leg press and 2–4 pounds more on bench press than before, while the placebo group didn’t change [24].

A longer trial showed what happens when that advantage compounds.

Over 24 weeks, postmenopausal women who combined creatine with resistance training improved leg-press strength by roughly 20% and bench press by 10% — about twice the gains of women who trained without the supplement [25].

For perspective, thigh strength has been shown to drop by about 10% within a single year after menopause — a precipitous decline driven by hormonal and mitochondrial slowdown [26]. By restoring some of the energy efficiency estrogen once supported, creatine helps offset that loss.*

How does creatine affect bone health after menopause?

Estrogen shapes the very architecture of bone.

Bone is living tissue, constantly dismantled and rebuilt. And just as with muscle, estrogen regulates the energy behind that renewal. It keeps bone turnover in balance by restraining osteoclasts, the cells that break bone down, while supporting osteoblasts, the ones that rebuild it.

When estrogen falls, that control slips. Osteoclasts become overactive, chewing through bone faster than it can be replaced. The microscopic lattice that gives bone its strength begins to thin, and fractures become more likely. In the first five years after menopause, women lose roughly 10% of their bone density — the fastest skeletal aging the human body ever experiences [27].

All of this ties back to energy. Building bone is metabolically costly work. Osteoblasts burn through ATP to synthesize collagen and mineralize the matrix.

Could creatine help offset that energetic strain?

In early lab studies, adding creatine to osteoblast cultures accelerated their maturation and mineralizing activity — essentially teaching bone-forming cells to build faster and stronger [28].

The question was put to the test over twelve months in postmenopausal women who trained three times a week while taking either creatine or placebo [29].

In the placebo group, bone at the femoral neck — a fracture hotspot — thinned by almost 4%. In the creatine group, the loss was closer to 1%. For perspective, a 5% drop in bone density has been linked to about a 25% higher fracture risk [30].

But not all of these studies tell the same story. In another trial, women took creatine faithfully for two years, yet they saw no beneficial differences in their bones [31].

Why? In this group, there was no resistance training.

Bone needs strain to know it should rebuild. Mechanical loading directs the energy towards rebuilding. Creatine amplifies the body’s building response, but it can’t start the conversation by itself. You still need the weight on the bar.*

How does creatine affect mood in women?

Women experience low mood far more often than men — about 60% more, by some estimates [32]. It’s one of the most consistent findings in mental health research.

The reasons for this, of course, are layered. But part of the explanation may come down to energy, and how sex hormones shape the brain’s ability to manufacture and distribute it.

Early imaging work suggested that women carry less creatine in the frontal lobe — the region that governs focus and emotional control — and one of the brain’s most energy-demanding systems [33].

More recent studies, however, reveal a more nuanced picture.

Brain creatine levels weren’t necessarily lower in women vs men. Instead, creatine in the prefrontal cortex fluctuated across the menstrual cycle, shifting in a hemisphere-specific rhythm [34]. In other words, the female brain’s energy reserve moves with its hormones.

That’s notable because mood shifts tend to cluster around hormonal transitions — puberty, the days before menstruation, and after pregnancy [35].

Could directly boosting mental energy steady this energetic turbulence?

In a clinical trial from the University of Utah, adolescent girls took various doses of creatine monohydrate or placebo for eight weeks [36]. Using phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy, researchers measured phosphocreatine in the frontal lobe.

Sure enough, creatine supplementation increased phosphocreatine in a clear dose-dependent pattern:

+4.2% at 2 g per day

+8.8% at 4 g

+9.1% at 10 g

Increases in stored creatine (i.e., phosphocreatine) correlated with improvements in mood scores, linking higher brain energy reserves with better emotional stability. By reinforcing the brain’s energy buffer, creatine may help steady the mind through hormonal highs and lows.*

How does creatine affect cognition in perimenopause and menopause?

Cognitive changes, such as brain fog and memory lapses, are among the most reported — and least understood — effects of perimenopause [37].

Nearly two-thirds of women report subjective cognitive problems during the transition, and these aren’t just “in their head.” They correlate with measurable declines. Longitudinal testing shows that during perimenopause, women fail to improve on memory and processing tests that normally strengthen with practice [38].

The same creatine–phosphocreatine circuit that powers muscle contraction also fuels thought. Neurons use it to regenerate ATP between bursts of activity, keeping energy delivery steady through the brain’s constant workload. When that buffering capacity slips, performance does too. And that’s precisely where creatine shines.*

A new double-blind trial gave that idea a real-world check [39].

A group of perimenopausal and menopausal women took small daily doses of creatine hydrochloride for four weeks. In participants taking 1.5 grams of creatine per day, reaction time improved roughly 5-times more than placebo (6.6% vs. 1.2%).

Reaction time may sound trivial, but it’s one of the brain’s most energy-hungry tasks, translating perception into action in fractions of a second. Each response draws on multiple brain systems at once, burning through ATP at every link in the chain. When reaction time improves, it’s not merely faster reflexes, it’s a sign the brain is using energy more efficiently.

Using magnetic resonance spectroscopy, researchers measured metabolite levels in the brain. They found that frontal lobe creatine rose by 16% in the same group, while remaining flat in placebo. It was a visible shift in the brain’s energetic balance, driven by a small daily dose of creatine.*

When hormonal transitions raise the metabolic cost of thinking, a stronger phosphocreatine buffer may help the brain stay sharp and steady.

How much creatine should women take?

The Basics: Daily Dosing and Loading

If you want faster results, start with a loading phase.

The quickest way to raise muscle creatine stores is by taking 20 grams per day, usually split into four 5-gram servings [40].

After that, a steady 3–5 grams per day keeps levels topped off.

If you’re not in a hurry, you can skip the loading altogether. The same 3–5-gram daily dose will reach full saturation on its own. It just takes longer — usually three to four weeks instead of one.

For most people, the best choice is creatine monohydrate, the time-tested form used in nearly every major clinical study [41].

How Long Until You See Results?

Muscle responds first. It’s packed with creatine transporters that pull the molecule in quickly [42]. That’s why a week of loading — or a few weeks of steady dosing — can raise muscle creatine by 25–30%, and sometimes far more in people who start out with low levels [43].

The brain, on the other hand, plays gatekeeper. Creatine has to cross the blood–brain barrier, where transporters are sparse and tightly regulated [44]. The same dose still gets through — it just takes longer. Most studies only show measurable increases in brain creatine after three to four weeks, and even then the rise is much smaller, around 5–15% [45].

For this reason, some researchers suspect that higher or longer dosing (around 5–10 g per day) may be needed to reliably enhance brain creatine levels [46].

What If You Need Results Now?

Sometimes the brain needs backup today, not in three weeks.

For instance, during sleep loss or intense mental stress, phosphocreatine can drop fast, and thinking slows to a crawl.

In a controlled sleep lab study, healthy volunteers stayed awake for 21 hours straight — an obvious recipe for cognitive freefall [47].

But when they took a single high dose of creatine, the crash never came. On cognitive tests, participants processed logic and numbers about 25–30% faster, and held onto words and sequences that the placebo group forgot. The benefit wasn’t across the board — alertness still dipped — but energy-hungry tasks like reasoning and working memory were effectively protected.

Brain imaging showed that creatine stabilized phosphocreatine levels and even raised total brain creatine within a few hours, something that normally takes weeks.

How? Under metabolic stress, the brain seems to relax its usual control over creatine transport. When energy demand spikes and ATP starts to drop, those tight gates at the blood–brain barrier loosen just enough for more creatine to get through — allowing it to act as an emergency power reserve.

It’s not a routine protocol, but a single high dose (~20 grams) has been shown in lab settings to temporarily support cognitive performance in the face of sleep loss and mental strain.*

Advanced Science, Advanced Creatine

Experience creatine redefined — because a strong body and mind are possible at any age. Whether you’re lifting heavier, thinking sharper, recovering faster, or aging with strength, Qualia Creatine+ was designed for you. Most creatine supplements skip the science that makes them truly effective — we didn’t. We combined premium, research-backed ingredients to deliver next-level energy, resilience, and clarity. This is creatine, perfected. Shop Qualia Creatine+.*

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

References

[1] Y. Su, Mol. Metab. 100 (2025) 102228.

[2] R.B. Kreider, D.S. Kalman, J. Antonio, T.N. Ziegenfuss, R. Wildman, R. Collins, D.G. Candow, S.M. Kleiner, A.L. Almada, H.L. Lopez, J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 14 (2017) 18.

[3] C. Rae, A.L. Digney, S.R. McEwan, T.C. Bates, Proc. Biol. Sci. 270 (2003) 2147–2150.

[4] J.T. Brosnan, M.E. Brosnan, Annu. Rev. Nutr. 27 (2007) 241–261.

[5] S.C. Kalhan, L. Gruca, S. Marczewski, C. Bennett, C. Kummitha, Amino Acids 48 (2016) 677–687.

[6] M.Y. Solis, G.G. Artioli, M.C. García Otaduy, C.C. Leite, W. Arruda, R.R. Veiga, B. Gualano, J. Appl. Physiol. 123 (2017) 407–414.

[7] A.M. Forsberg, E. Nilsson, J. Werneman, J. Bergström, E. Hultman, Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 81 (1991) 249–256.

[8] L.M. Stead, K.P. Au, R.L. Jacobs, M.E. Brosnan, J.T. Brosnan, Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 281 (2001) E1095–E1100.

[9] M. Wyss, R. Kaddurah-Daouk, Physiol. Rev. 80 (2000) 1107–1213.

[10] M. Joncquel-Chevalier Curt, P.M. Voicu, M. Fontaine, A.F. Dessein, N. Porchet, K. Mention-Mulliez, D. Dobbelaere, G. Soto-Ares, D. Cheillan, J. Vamecq, Biochimie 119 (2015) 146–165.

[11] A.E. Smith-Ryan, H.E. Cabre, J.M. Eckerson, D.G. Candow, Nutrients 13 (2021) 877.

[12] S.J. Ellery, D.W. Walker, H. Dickinson, Amino Acids 48 (2016) 1807–1817.

[13] N.S. Stachenfeld, Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 36 (2008) 152–159.

[14] S.R. Moore, A.N. Gordon, H.E. Cabre, A.C. Hackney, A.E. Smith-Ryan, Nutrients 15 (2023) 429.

[15] D. Häussinger, E. Roth, F. Lang, W. Gerok, Lancet 341 (1993) 1330–1332.

[16] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, NCHS Data Brief, No. 436 (2022).

[17] E. Benge, M. Pavlova, S. Javaheri, Front. Sleep 3 (2024) 1322761.

[18] S. Baltic, E. Grasaas, S.M. Ostojic, Nutr. Health 31 (2024) 369–376.

[19] A.J. Aguiar Bonfim Cruz, S.J. Brooks, K. Kleinkopf, C.J. Brush, G.L. Irwin, M.G. Schwartz, D.G. Candow, A.F. Brown, Nutrients 16 (2024) 2772.

[20] K. Shioda, K. Goto, S. Uchida, Sleep Biol. Rhythms 17 (2019) 27–35.

[21] M. Dworak, T. Kim, R.W. McCarley, R. Basheer, J. Sleep Res. 26 (2017) 377–385.

[22] A. Geraci, R. Calvani, E. Ferri, E. Marzetti, B. Arosio, M. Cesari, Front. Endocrinol. 12 (2021) 682012.

[23] A. Pellegrino, P.M. Tiidus, R. Vandenboom, Sports Med. 52 (2022) 2853–2869.

[24] L.A. Gotshalk, W.J. Kraemer, M.A. Mendonca, J.L. Vingren, A.M. Kenny, B.A. Spiering, D.L. Hatfield, M.S. Fragala, J.S. Volek, Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 102 (2008) 223–231.

[25] B. Gualano, A.R. Macedo, C.R. Alves, H. Roschel, F.B. Benatti, L. Takayama, A.L. de Sá Pinto, F.R. Lima, R.M. Pereira, Exp. Gerontol. 53 (2014) 7–15.

[26] J.P. Greeves, N.T. Cable, T. Reilly, C. Kingsland, Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 97 (1999) 79–84.

[27] P. Anagnostis, J.K. Bosdou, K. Vaitsi, D.G. Goulis, I. Lambrinoudaki, Hormones 20 (2021) 13–21.

[28] I. Gerber, I. ap Gwynn, M. Alini, T. Wallimann, Eur. Cell Mater. 10 (2005) 8–22.

[29] P.D. Chilibeck, D.G. Candow, T. Landeryou, M. Kaviani, L. Paus-Jenssen, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 47 (2015) 1587–1595.

[30] G.H. Guyatt, A. Cranney, L. Griffith, S. Walter, N. Krolicki, M. Favus, C. Rosen, Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 31 (2002) 659–679.

[31] L.P. Sales, A.J. Pinto, S.F. Rodrigues, J.C. Alvarenga, N. Gonçalves, M.M. Sampaio-Barros, F.B. Benatti, B. Gualano, R.M.R. Pereira, J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75 (2020) 931–938.

[32] S.H. Li, B.M. Graham, Lancet Psychiatry 4 (2017) 73–82.

[33] S. Riehemann, H.-P. Volz, B. Wenda, G. Hübner, G. Rößger, R. Rzanny, H. Sauer, NMR Biomed. 12 (1999) 483–489.

[34] H. Hjelmervik, M. Hausmann, A.R. Craven, M. Hirnstein, K. Hugdahl, K. Specht, Neuroimage 172 (2018) 817–825.

[35] P.R. Albert, J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 40 (2015) 219–221.

[36] D.G. Kondo, L.N. Forrest, X. Shi, Y.H. Sung, T.L. Hellem, R.S. Huber, P.F. Renshaw, Amino Acids 48 (2016) 1941–1954.

[37] G.A. Greendale, A.S. Karlamangla, P.M. Maki, JAMA 323 (2020) 1495–1496.

[38] G.A. Greendale, M.H. Huang, R.G. Wight, T. Seeman, C. Luetters, N.E. Avis, J. Johnston, A.S. Karlamangla, Neurology 72 (2009) 1850–1857.

[39] D. Korovljev, J. Ostojic, J. Panic, M. Ranisavljev, N. Todorovic, D. Nedeljkovic, J. Kuzmanovic, M. Vranes, V. Stajer, S.M. Ostojic, J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. (2025) 1–12.

[40] A.E. Smith-Ryan, G.M. DelBiondo, A.F. Brown, S.M. Kleiner, N.T. Tran, S.J. Ellery, J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 22 (2025) 2502094.

[41] G. Escalante, A.M. Gonzalez, D. St Mart, M. Torres, J. Echols, M. Islas, B.J. Schoenfeld, Heliyon 8 (2022) e12113.

[42] D.G. Candow, S.M. Ostojic, S.C. Forbes, J. Antonio, Adv. Exerc. Health Sci. 1 (2024) 99–107.

[43] E. Hultman, K. Söderlund, J.A. Timmons, G. Cederblad, P.L. Greenhaff, J. Appl. Physiol. 81 (1996) 232–237.

[44] D.G. Candow, S.C. Forbes, S.M. Ostojic, K. Prokopidis, M.S. Stock, K.K. Harmon, P. Faulkner, Sports Med. 53 (Suppl. 1) (2023) 49–65.

[45] P. Dechent, P.J.W. Pouwels, B. Wilken, F. Hanefeld, J. Frahm, Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 277 (1999) R698–R705.

[46] N. Fabiano, D. Candow, J. Psychiatry Brain Sci. 10 (2025) e250006.

[47] A. Gordji-Nejad, A. Matusch, S. Kleedörfer, H.J. Patel, A. Drzezga, D. Elmenhorst, F. Binkofski, A. Bauer, Sci. Rep. 14 (2024) 4937.

Written by

Written by