Every workout begins with your cells falling into energy debt.

That debt is what drives mitochondrial biogenesis, the process by which exercise forces your cells to remodel their mitochondria and ultimately enhance mitochondrial health.

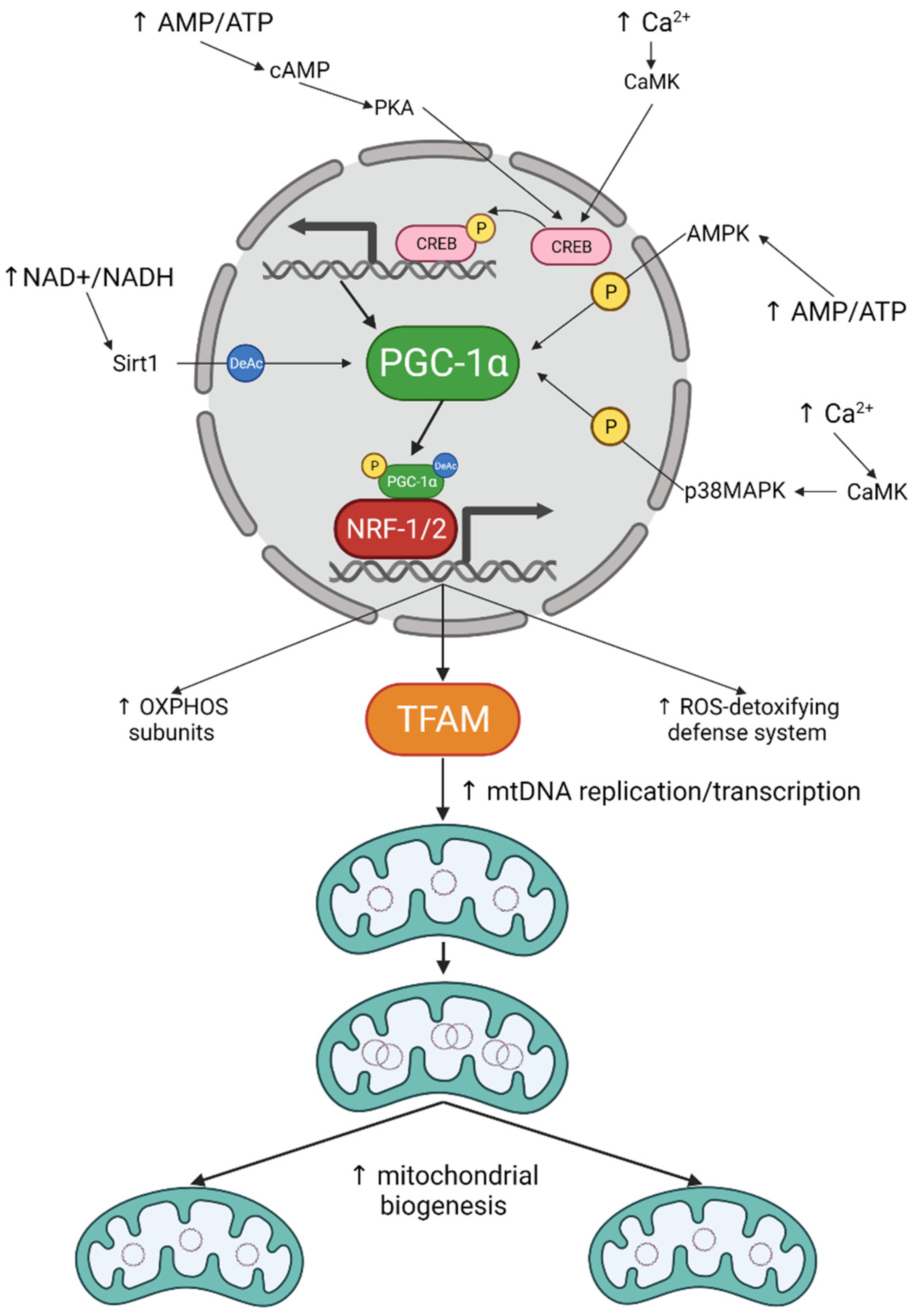

The moment you start moving, your muscles burn through ATP faster than they can replace it. That shortfall acts like an alarm signal, flipping on PGC-1α, the molecular switch that tells the cell to upgrade its power grid [1]. Within weeks, each muscle fiber holds more mitochondrial machinery than it did before — more hardware your body can use to make energy, and one of the clearest markers of mitochondrial health.

But mitochondrial biogenesis isn’t just about adding volume. Exercise also changes how well the machinery runs.

One such adaptation is a rise in respiratory capacity. Mitochondria get better at turning oxygen into ATP, like a tuned engine squeezing more power from the same fuel.

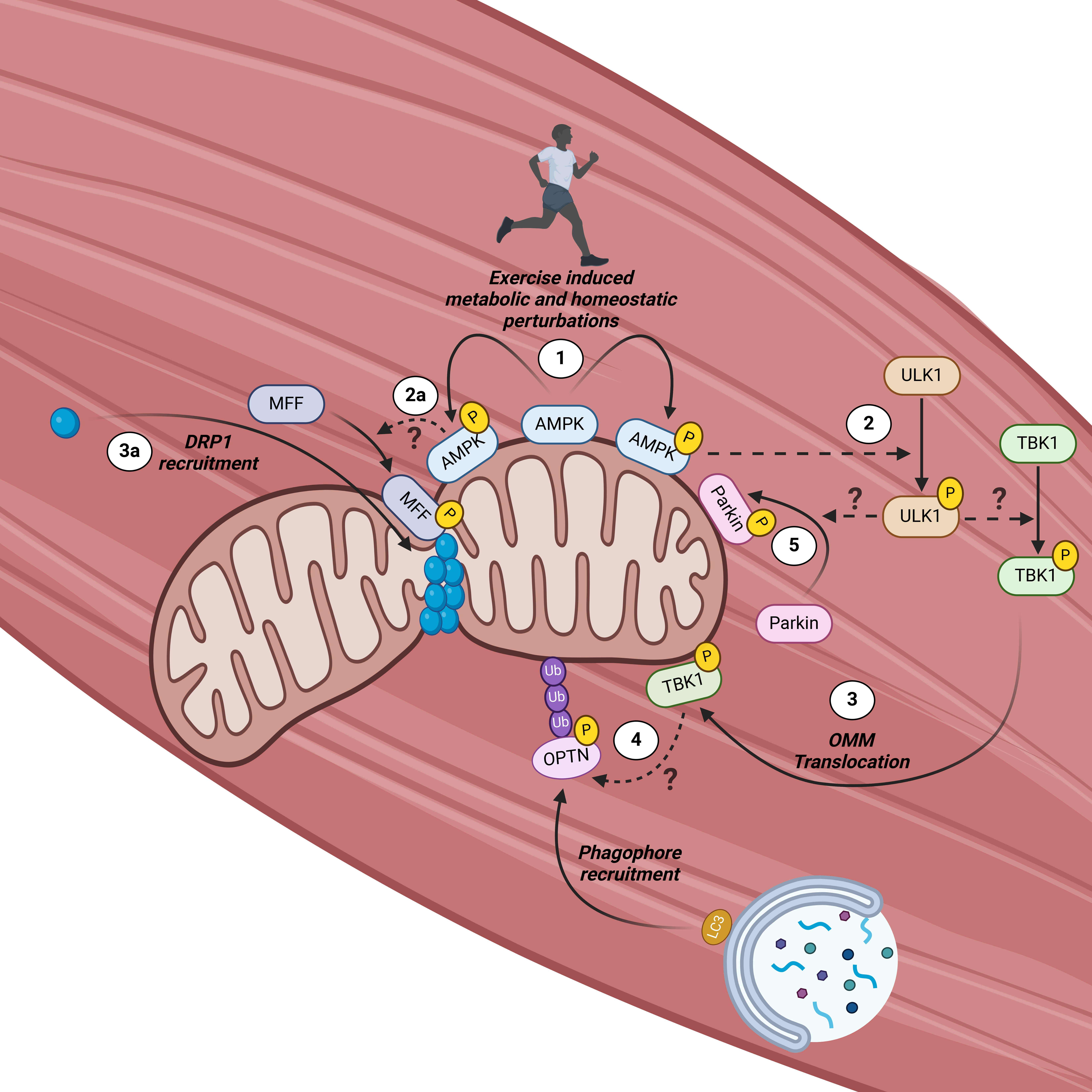

At the same time, the cell tightens quality control. Exercise boosts the proteins that govern mitochondrial fission and fusion, allowing damaged pieces to be cut away and healthy ones to merge. It also boosts mitophagy — the selective clearing of worn-out mitochondria — resulting in a network that’s cleaner and better able to withstand metabolic stress [2].

And these microscopic upgrades scale into real-world performance.

Across dozens of studies, increases in mitochondrial density and increases in VO₂max rise in parallel — when VO₂max goes up, mitochondrial machinery increases by almost the exact same percentage [3].

That relationship matters far beyond sport.

In a 122,000-person study, cardiorespiratory fitness showed a stronger link to long-term survival than smoking, and the fittest individuals had an 80% lower risk of death — with no upper limit of benefit. The greater the fitness, the lower the risk [4].

Why? Because improving mitochondrial density and function strengthens every organ system that depends on a reliable energy supply — which is all of them.

But “exercise” isn’t a single stimulus. Different kinds of exercise place different stresses on the cell, and the mitochondrial network reshapes itself accordingly.

So the real question is: what mix of training builds the most powerful and durable energy system?

To find the answer, it helps to look at those whose cells already operate on the edge of human performance.

C. Cardanho-Ramos, V.A. Morais, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021) 13059. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Figure 1 reproduced with permission [5].

Why Mitochondrial Health Matters

If you want to see human metabolism at full tilt, check out the people who live on the far right side of the curve: athletes.

Across studies, they show the highest mitochondrial density and function ever measured in humans. In one analysis, citrate synthase activity — a proxy for mitochondrial content — was nearly double in elite athletes compared to physically active non-elite counterparts [6].

A skeptic might shrug and say: sure, but they won the genetic lottery.

Except mitochondria aren’t fixed traits. They’re one of the most plastic systems in the body, constantly remodeling in response to the signals we give them.

We saw the first hint of this in the 1960s, when scientists built miniature treadmills for rats and made them run. After only a few weeks, the animals’ mitochondrial enzymes had nearly doubled [7].

Humans show similar responsiveness. In a now-classic study, cycling four hours a week for three months increased oxidative capacity by ~95% — proof that the same machinery can be rebuilt in us too [8].

This adaptability matters even more with aging. Older adults do lose oxidative power, but the decline isn’t fixed. Endurance-trained older adults have oxidative enzyme levels nearly indistinguishable from younger trained athletes, and roughly double those of sedentary peers [9].

And this translates to real health improvements.

In overweight adults, three months of aerobic training boosted the fraction of each muscle fiber occupied by mitochondria by ~76%, and these increases tracked almost one-to-one with improvements in insulin sensitivity [10].

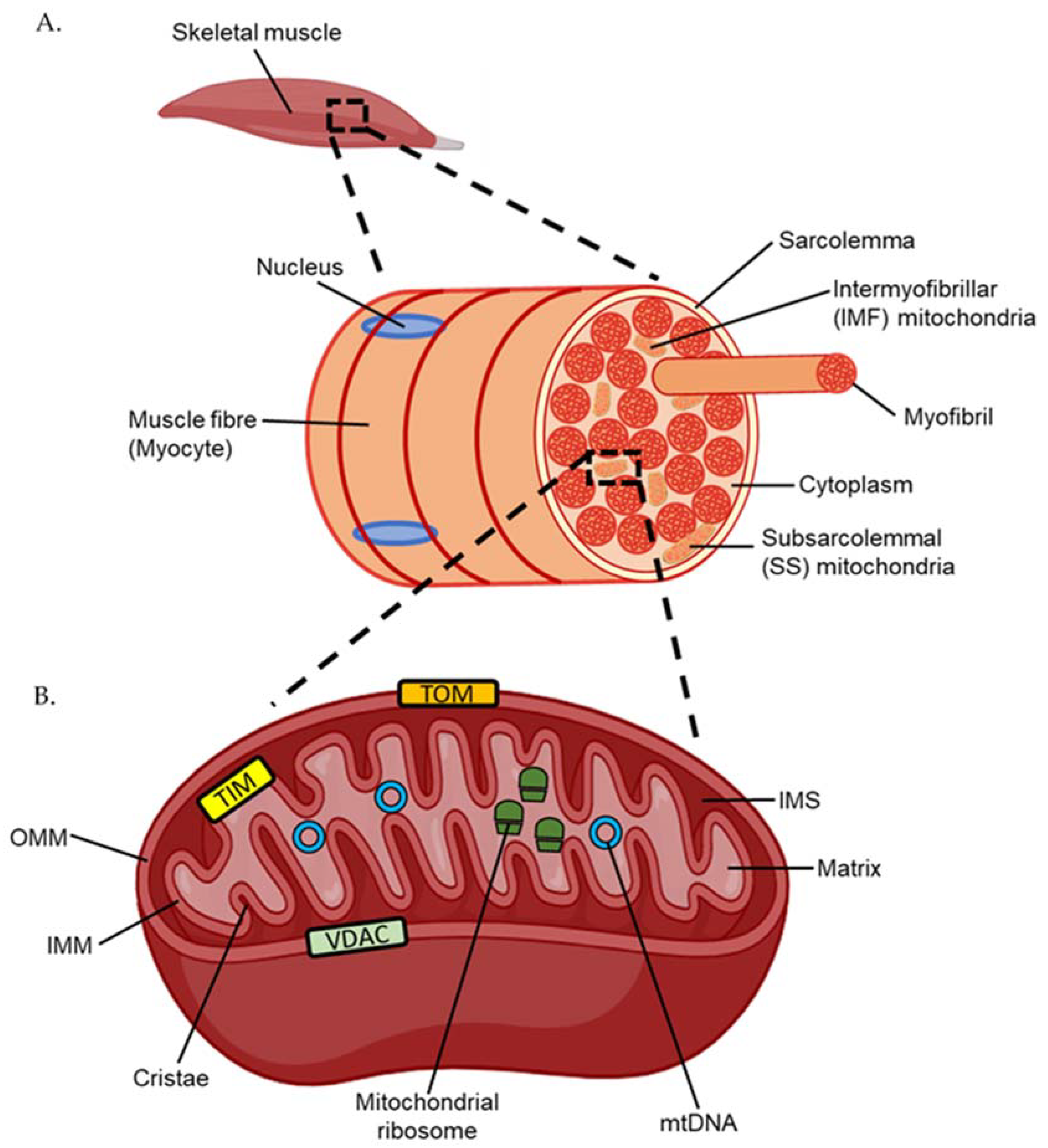

D.F. Taylor, D.J. Bishop, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022) 1517. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Figure 1 reproduced with permission [1].

Even more remarkably, these benefits aren’t confined to muscle. Aerobic training also upgrades mitochondrial machinery in the brain.

In rodents, regular aerobic training increases mitochondrial biogenesis across major brain regions — including the hippocampus, a key hub for learning and memory — suggesting that the same workouts that strengthen physical endurance also upgrade the brain’s energy system [11].

Rather than being products of destiny, athletes emerge from long-term, repeated stimulus. Their mitochondria look the way they do because of the inputs they repeat. And that is where we turn next.

The Volume Effect: How Endurance Training Increases Mitochondrial Density

Long before anyone could sequence mitochondrial DNA, physiologists already knew endurance was closely tied to mitochondrial abundance.

In the 1950s, Paul and Sperling dissected the flight muscles of birds, and stumbled upon an almost comical contrast: species that fly for hours had nearly ten times the mitochondrial enzyme activity of birds that barely leave the ground [12].

Decades later, accumulated evidence has borne this out.

In a meta-analysis of 56 exercise studies, Granata and colleagues found that total training volume — not exercise intensity — was the strongest predictor of mitochondrial content [13]. As weekly minutes increased, citrate synthase — a key mitochondrial enzyme that supports the cell’s capacity for aerobic energy production — rose in parallel. Because citrate synthase reliably scales with mitochondrial content, researchers commonly measure its activity as a biochemical marker of mitochondrial activity and density.

For instance, in one trial, bumping weekly training time from ~1 hour to ~4 hours produced nearly four-fold greater mitochondrial gains [14].

Animal work reinforces that dose–response curve in even sharper resolution. In slow-twitch fibers — the true endurance engines — citrate synthase activity just keeps climbing with greater training loads, with no ceiling in sight [15].

Stack enough low-intensity, repeatable aerobic time, and the muscle thickens its cellular power grid. And once that grid has expanded, a new bottleneck emerges: not how much mitochondria you have, but how effectively they work [16].

The Intensity Effect: How High-Intensity Exercise Improves Mitochondrial Health

In their analysis, Granata and colleagues found that training volume was the strongest predictor of mitochondrial content. Relative exercise intensity, in contrast, did not independently predict increases in citrate synthase activity [14].

But when Granata’s team looked at mitochondrial respiration — each mitochondrion’s ability to turn oxygen into usable energy — the signal flipped. The biggest improvements came from harder efforts.

You see this clearly in head-to-head trials.

In one experiment, participants spent four weeks doing steady cycling or all-out sprints. Only the sprint group improved mitochondrial respiration, with a 25% jump in oxygen-consuming capacity. Yet their citrate synthase didn’t move at all. In other words, they didn’t grow more mitochondria. They forged better ones [17].

Why? Because hard efforts trigger a fundamentally different biochemical message.

During intense work, energy demand outruns supply. ATP plummets. Calcium spikes. Oxygen delivery falls behind. The cell reads this as a warning that the current machinery is near its limit [18].

The subsequent response is profound.

Signals controlling mitochondrial quality control — fission, fusion, and mitophagy — switch on within hours. Fission trims and isolates damaged segments. Fusion knits healthy mitochondria together. Mitophagy removes debris. In effect, hard efforts summon a renovation crew that dismantles weak links and rebuilds a more efficient, better-connected network [19].

E.J. Ritenis, C.S. Padilha, M.B. Cooke, C.G. Stathis, A. Philp, D.M. Camera, Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 328 (2025) E198–E209. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Figure 2 reproduced with permission [20].

This matters for performance, but also for health. A mitochondrial network that is regularly pruned will leak fewer free radicals and resist the metabolic slowdown associated with aging [2].

Put the pieces together and the pattern is unmistakable: volume builds the grid and intensity upgrades the engines.

And this pairing happens to be exactly how elite endurance athletes train. Analyses of top competitors repeatedly show a polarized distribution: roughly 80% easy, conversational aerobic work punctuated by brief, structured high-intensity bouts [21].

This pattern stimulates both sides of mitochondrial adaptation — expansion and refinement — in the proportions biology rewards.

How to Train Your Mitochondria: Evidence-Based Guidelines

Build Mitochondrial Density With Aerobic Base Training

When you accumulate enough low-intensity volume, the muscle responds by expanding its oxidative infrastructure.

In the largest analysis of its kind (353 studies involving nearly 6,000 participants), programs built around ~4 sessions per week and 3–5 hours of easy aerobic work produced roughly 23% increases in mitochondrial content as well as 13% gains in capillary density [22].

That vascular expansion is key. New mitochondria can’t operate at full capacity unless oxygen delivery grows with them. At these workloads, VO₂max improves by ~10%, reflecting the combined effect of more engines (mitochondria) and more plumbing (capillaries).

Practical target: Aim for 3–5 hours per week of steady, conversational-pace aerobic training, ideally in at least 45–75-minute bouts.

Use High-Intensity Intervals to Improve Mitochondrial Efficiency

Where steady aerobic work expands the mitochondrial network, harder efforts refine it. A single high-intensity interval session triggers a biochemical surge that activates PGC-1α and the pathways behind mitochondrial turnover and repair.

The effect is potent even in small doses.

In sedentary middle-aged adults, six sessions of 10×1-minute intervals at ~80–95% max HR raised oxidative enzymes by ~35%, elevated PGC-1α by ~56%, and improved insulin sensitivity [23].

All of this was achieved with only ~60 minutes of total work across two weeks.

Practical target: Include 1–2 weekly interval sessions. These brief spikes upgrade mitochondrial efficiency and quality control in ways volume alone cannot.

Consistency: The Key to Maintaining Mitochondrial Adaptations

Mitochondria adapt quickly because they’re built to scale with demand. But that same responsiveness makes them fragile.

The structural gains (density) rely on repetition. Remove the signal, and the system begins to unwind. In one study, cyclists who increased mitochondrial enzymes and respiratory capacity by nearly 50% during a high-volume block lost most of those gains within two weeks of reduced training [24].

Earlier work found the same pattern: a 70% increase in energy production after six weeks of training fell back toward baseline after just three weeks without regular exercise [25].

And the functional side is even more sensitive. Mitochondrial respiration can drop by one-third after a single week of inactivity, even in elite athletes [26].

Taken together, the lesson is clear: mitochondria are highly trainable but profoundly perishable. They grow in the presence of repeated stress and shrink when that stress disappears. In that sense, mitochondria are a perfect microcosm of fitness itself.

That’s why athletes are such valuable models. Their value isn’t in the intensity of their training but in its predictability. They demonstrate, in real time, how repeated stress creates and preserves mitochondrial capacity.

Practical target: Choose aerobic habits you can repeat every week. The specific modality doesn’t matter as much as whether you can stick with it, because consistency is the true driver of lasting mitochondrial fitness.

References

[1] D.F. Taylor, D.J. Bishop, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022) 1517.

[2] J.R. Huertas, R.A. Casuso, P.H. Agustín, S. Cogliati, Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019 (2019) 7058350.

[3] A. Vigelsø, N.B. Andersen, F. Dela, Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 6 (2014) 84–101.

[4] K. Mandsager, S. Harb, P. Cremer, D. Phelan, S.E. Nissen, W. Jaber, JAMA Netw. Open 1 (2018) e183605.

[5] C. Cardanho-Ramos, V.A. Morais, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021) 13059.

[6] R.A. Jacobs, C. Lundby, J. Appl. Physiol. 114 (2013) 344–350.

[7] J.O. Holloszy, J. Biol. Chem. 242 (1967) 2278–2282.

[8] P.D. Gollnick, R.B. Armstrong, B. Saltin, C.W. Saubert IV, W.L. Sembrowich, R.E. Shepherd, J. Appl. Physiol. 34 (1973) 107–111.

[9] D.N. Proctor, W.E. Sinning, J.M. Walro, G.C. Sieck, P.W. Lemon, J. Appl. Physiol. 78 (1995) 2033–2038.

[10] F.G.S. Toledo, S. Watkins, D.E. Kelley, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91 (2006) 3224–3227.

[11] J.L. Steiner, E.A. Murphy, J.L. McClellan, M.D. Carmichael, J.M. Davis, J. Appl. Physiol. 111 (2011) 1066–1071.

[12] M.H. Paul, E. Sperling, Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 79 (1952) 352–354.

[13] C. Granata, N.A. Jamnick, D.J. Bishop, Sports Med. 48 (2018) 1809–1828.

[14] D. Montero, C. Lundby, J. Physiol. 595 (2017) 3377–3387.

[15] D.J. Bishop, C. Granata, N. Eynon, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1840 (2014) 1266–1275.

[16] J. Nielsen, K.D. Gejl, M. Hey-Mogensen, H.C. Holmberg, C. Suetta, P. Krustrup, C.P.H. Elemans, N. Ørtenblad, J. Physiol. 595 (2017) 2839–2847.

[17] C. Granata, R.S. Oliveira, J.P. Little, K. Renner, D.J. Bishop, FASEB J. 30 (2016) 959–970.

[18] C.G. Perry, J. Lally, G.P. Holloway, G.J. Heigenhauser, A. Bonen, L.L. Spriet, J. Physiol. 588 (2010) 4795–4810.

[19] C.L. Axelrod, C.E. Fealy, A. Mulya, J.P. Kirwan, Acta Physiol. 225 (2019) e13216.

[20] E.J. Ritenis, C.S. Padilha, M.B. Cooke, C.G. Stathis, A. Philp, D.M. Camera, Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 328 (2025) E198–E209.

[21] K.S. Seiler, G. Kjerland, Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 16 (2006) 49–56.

[22] K.S. Mølmen, N.W. Almquist, Ø. Skattebo, Sports Med. 55 (2025) 115–144.

[23] M.S. Hood, J.P. Little, M.A. Tarnopolsky, F. Myslik, M.J. Gibala, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43 (2011) 1849–1856.

[24] C. Granata, R.S. Oliveira, J.P. Little, K. Renner, D.J. Bishop, FASEB J. 30 (2016) 3413–3423.

[25] R. Wibom, E. Hultman, M. Johansson, K. Matherei, D. Constantin-Teodosiu, P.G. Schantz, J. Appl. Physiol. 73 (1992) 2004–2010.

[26] D.L. Costill, W.J. Fink, M. Hargreaves, D.S. King, R. Thomas, R. Fielding, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 17 (1985) 339–343.

Written by

Written by